Jeff Davis, January 2010

The below text is from "Gas Engines and Producers", Marks.

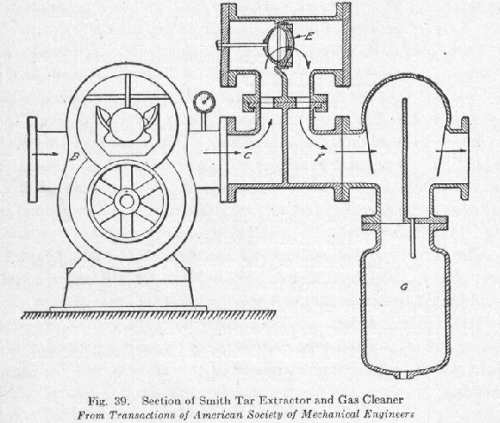

The apparatus shown in Fig. 39 is a recent development in gas cleaning.

With this type of apparatus the standard anthracite producer is used with bituminous coal and no attempt is made to fix the resulting tar.

The raw gas, on leaving the producer, is first cooled to a point where tar vapors are condensed, by being passed through a primary cooler or condenser, from which the gas is carried into a rotary gas pump or exhauster B which delivers it under pressure into the main C. It is then delivered through a porous diaphram of spun glass E into the engine main F where a sump or separator G is provided in which the tar accumulates.

The diaphragm must be sufficiently porous to permit the gas and tar to pass freely and is in the form of a uniform layer of glass wool retained between two metal screens. Ordinarily, the thickness is about one-quarter of an inch and the diameter must be adjusted in accordance with the quantity of the gas to be treated ordinarily four hundred cubic feet per hour can be handled per square inch of diaphragm area. No tar is retained in the diaphragm, both tar and gas being discharged together, but in passing through, an important change in the physical state of the tar occurs. On the entering side, the tar exits in the form of a large number of minute particles, known as tar fog, while in passing the diaphragm these particles are caused to coalesce so that on the discharge side the tar particles are of relatively large dimensions so large, in fact, that they can no longer be carried forward in the gas current and immediately separate out by gravity and drain into the sump.

It appears to be possible to secure any desired degree of gas cleanness simply by regulating the velocity of flow through the diaphragm, i.e., the pressure maintained across the diaphragm. In ordinary commercial operation, it is found that a difference in pressure of from 2.5 to 4 pounds per square inch will clean the gas to such an extent that no discoloration will be produced on a white filter paper through which 30 cubic feet of gas has been passed.

This is not a filter process, since, for the best separation by filtration, the velocity must be low and the material separated out remains in the filter. No water is used in connection with this process except that required to cool the gas, and as a consequence there is no formation of tar emulsion therefore the tar separated is practically water free (less than 1 percent) and may easily be burned. The gas must be cooled only sufficiently to completely condense the tar vapors, since any further cooling will increase the viscosity of the tar and consequently the resistance through the diaphragm which must be a minimum. This process is not well adapted for use on gas containing large quantities of lampblack or from coals yielding a very heavy, viscous tar. It has, however, been used with great success with Ohio, Illinois, and Indiana high-volatile coals and with lignite.

The theory of the operation of this extractor is not definitely known, but it is supposed that it is the result of some electrical action caused by the impact and fluid friction against the glass wool.

This apparatus has also been used with marked success for cleaning gas made from anthracite coal, giving giving a much cleaner gas with a lower water consumption than can be obtained by other methods."

Jeff also did some patent mining:

http://www.google.com/patents/about?id=_9xTAAAAEBAJ&dq=1544950

http://www.google.com/patents/about?id=qe5oAAAAEBAJ&dq=1379056

http://www.google.com/patents/about?id=c3VJAAAAEBAJ&dq=1140198

http://www.google.com/patents/about?id=WW9PAAAAEBAJ&dq=1348966>